Last weekend I was at a symposium in Bath celebrating 50 years of the Biological Records Centre (BRC). The BRC collates and manages species observation data, including supporting biological recording schemes in publishing atlases, developing and hosting online resources. I have a long interest in biological recording, as a child spending most of my weekends and school holidays recording wildlife in a local woodland, but it was always on my own. It has not been until the last few years I have become interested in ‘formal’ biological recording by joining schemes and societies, much of this has been helped by the emergence of the internet in allowing me to make contact with like-minded people. Many of the talks at the symposium were of interest to me not only as a biological recorder but had some relevance to my future PhD research as the species distribution data held by the BRC have been used to understand responses to environmental change. I had my usual anxiety about attending but was at least confident I would know some delegates already, even if just through the internet, with the useful icebreaker “I follow you on Twitter” at the ready. There was an additional challenge in that I forgot to book my accommodation at the venue so ended up staying in a hostel in the city. I had never stayed in a dormitory before and was very concerned at how I would cope, but thought of it as an ‘experience’ and reminded myself of my promise to ‘be scared but do it anyway’. In the event it was not too bad, although the noise and bright light of the surrounding bars made sleep difficult, but at least it was cheap!

|

| Saturday morning in Bath |

The symposium talks were on Friday afternoon and Saturday, and covered the range of ways biological recording data has been used to detect changes in species distribution, especially responses to climate change, and some of the problems involved in this. Biological data does not reflect constant effort, with bias in site and taxon selection etc. Data aggregation and selection, and computer modelling are some of the methods that can be used to detect the signals among the noise, all the talk of data and modelling got me very excited - I have definitely chosen the right PhD for me!

There were also thought-provoking lectures on citizen science, and on how technological developments have impacted and may impact on biological recording, including the use of molecular techniques in species identification and monitoring.

|

| The cake was tasty too! |

The highlight of the weekend was a Sunday fieldtrip to Salisbury Plain Defence Training Estate, a military site not open to the public. It is the largest area unimproved chalk downland in north west Europe, with 20,000 hectares of Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) and Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) making it the largest designated site in the United Kingdom. Delegates with a wide range of interests in biological recording boarded two coaches for an escorted trip around the site, stopping at four areas to hunt for their favourite group(s), discuss hot topics or just admire the glorious habitat. I really enjoy trips with people who study different groups as it is a great way to discover new species. I did not go with the intention of collecting a group myself, since I knew I would not have time to process them at the moment, but contented myself observing the scenery and diversity. Observing the observers was also interesting, and fun to deduce which groups(s) they are looking for based on the techniques they use. Botanists often got down on their knees to examine plants, ornithologists and photographers were loaded with cameras and binoculars, and entomologists of various sorts had their assorted nets, pooters and tubes. Those turning over stones and grubbing about often turned out to be woodlice or centipede recorders; also in this category were several members of the Earthworm Society of Britain (ESB), because digging was not permitted due to the risk of unexploded ordinance – a sad restriction for an earthworm recorder. Despite this at least four species were recorded by rummaging

in muddy puddles and turning over stones and other objects.

|

| Keiron and Vicky from the ESB make do with turning over stones to find earthworms on Salisbury Plain |

|

| Vicky and I with the first earthworm of the day, probably Apporectodea longa, found under a rusty drum |

Being a chalk download there were many woodlice and molluscs to be found under the stones, including the pill woodlouse Armadillidium vulgare, a species familiar to many for its defense of rolling up into a ball. Many of the specimens had babies, which develop from eggs in a special brood pouch on their underside.

|

| Armadillidium vulgare with young on Salisbury Plain |

Flowers and insects were everywhere, more than I have seen anywhere, and I get the feeling other chalk grasslands will never look so good again! Lepidoptera were everywhere, this thistle busy with Marbled Whites (Melanargia galathea), Burnet moths (Zygaena sp.) and assorted flies was typical. Other day-flying moths seen included the striking Forester (Adscita statices). I also saw some impressive flies including Cynomya mortuorum, my old favourite previously seen in Scotland,

and the huge black parasitoid fly Tachina grossa.

|

| Marbled Whites, Burnet moths and assorted flies nectaring on thistle |

|

| Forester on Greater Knapweed at Salisbury Plain |

I met a number of new plants, including Dwarf Spurge (Euphorbia exigua), the rare Tuberous Thistle (Cirsium tuberosum) and probably my most exciting plant of the day, Knapweed Broomrape (Orobanche elatior), a plant parasitic on Greater Knapweed (Centaurea scabiosa).

|

| Knapweed Broomrape (Orobanche elatior) on Salisbury Plain |

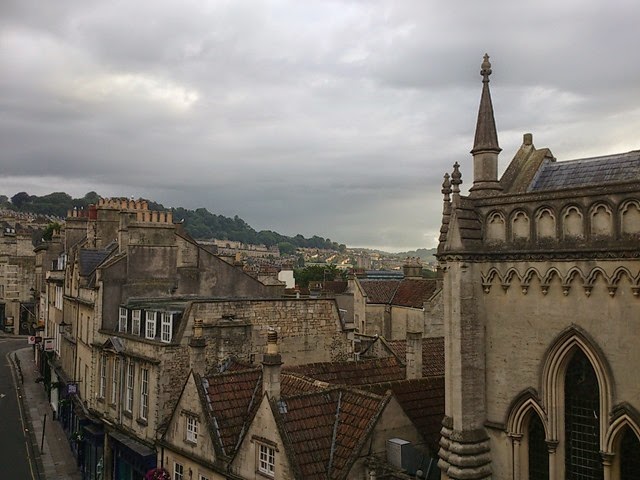

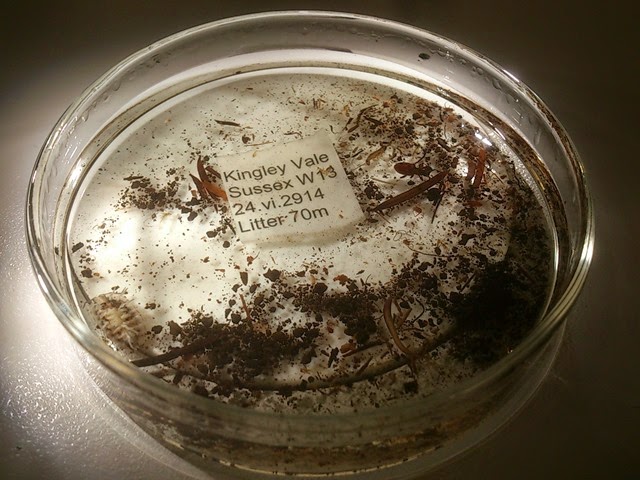

My most exciting invertebrate of the day was neither a fly nor an earthworm however, it was the Fairy Shrimp (Chirocephalus diaphanus) which I have wanted to see since I first learnt about it when I was around 5 years old. These shrimp are found in temporary pools, their eggs lying dormant when the pools dry out ready to hatch on the next heavy rain. It is protected under Schedule 5 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 but the trip organisers, who have a licence, had collected some in a jar for us to view.

|

| BRC 50th delegates huddle around temporary pools created by military vehicle manoeuvres to look for the elusive Fairy Shrimp |

|

| Fairy Shrimp (Chirocephalus diaphanus) |

The photograph through the container using my phone really does not do them justice. They were quite big, a couple of inches long with a translucent pinkish colour, swimming using beautiful undulating motions.

So in all it was a brilliant weekend, meeting new species (and people!) and giving me lots to think about for my own research. A big thanks to the organisers, and long may the BRC continue.

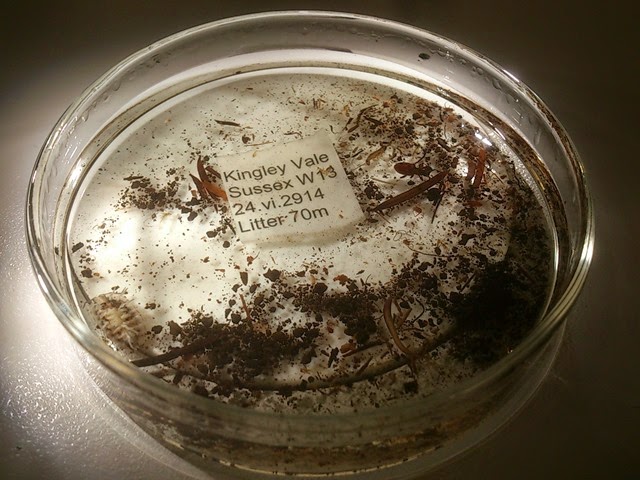

Quadrat assembled – sampling can begin!

Quadrat assembled – sampling can begin!